As a veteran operating room nurse, I’ve often drawn comparisons between flying a plane and supporting surgery. Both roles are high stakes, demand precision under pressure, and require a team working in sync. But one question I often reflect on is this:

How do we decide what we remember—and what we forget—in the operating room?

Why can I instantly recall how to respond to a hemorrhage, but still forget where one surgeon prefers the tower placed or what setting to select on a specific piece of equipment?

🔄 The Pilot’s QRH vs. The Nurse’s Experience

Pilots are trained to memorize what’s known as memory items—a set of actions committed to memory for emergency situations. These are rehearsed over and over again until they become automatic. Only after the immediate threat is addressed do they consult the Quick Reference Handbook (QRH), a structured guide of procedures for troubleshooting and recovery.

Operating room nurses, by contrast, often learn on the job. We rely on exposure, mentorship, repetition, and experience. There’s no QRH for us. What we do have are mental maps, team communication, and countless moments of trial, error, and reflection. We build memory not in a simulator, but in real-time.

But should we? Could a structured, role-specific handbook for scrub and scout nurses, with memory prompts and decision trees, accelerate learning and reduce error?

🧠 Why We Remember Some Things and Forget Others

Cognitive science tells us that memory is shaped by emotion, repetition, relevance, and pattern recognition. We remember what we do often, what is associated with stress (like a surgical fire), and what aligns with a pattern we already understand.

Research shows that procedural memory—the kind used to tie shoelaces or scrub for surgery—forms in a part of the brain called the basal ganglia. This is also responsible for what we call “autopilot” behavior—like driving home without consciously recalling the route (MIT Neuroscience, 2019).

That’s why, after more than a decade in the OR, I can anticipate when a surgeon will ask for suction, or when the scout will need to open extra swabs. It’s not guessing—it’s pattern recognition + procedural memory.

But memory is selective. According to Harvard psychologist Daniel Schacter, we remember what we encode deeply, often emotionally or via repetition—but forget details that lack personal salience or aren’t retrieved often. (Schacter, The Seven Sins of Memory).

So it’s no surprise that I can forget the tower attachment or settings a certain surgeon prefers—I’m not emotionally attached to that information, nor is it reinforced frequently in context.

🧪 Simulation: What We Can Learn from Pilots

Pilots undergo regular simulator training to test their responses to rare but critical scenarios—engine fires, cabin depressurization, bird strikes. These simulations are realistic, stress-inducing, and reinforce both memory and teamwork.

Operating rooms are beginning to adopt similar high-fidelity simulation-based education. In centers like Northwestern Simulation or Cedars-Sinai’s OR360, OR teams train together in lifelike crisis scenarios—practicing not only tasks, but communication, leadership, and debriefing.

“Fly the plane, silence the bell, read the checklist.”

—Classic pilot mantra

“A great OR team runs like a cockpit crew—clear roles, constant communication, and a shared goal: safety.”

—Dr. K. Rosten, OR educator

🧠 What If OR Nurses Had a QRH?

What if nurses had a Quick Reference Handbook tailored to their role, specialty, and learning stage? Imagine a scrub nurse’s QRH including:

-

Memory checklists for laparoscopic cholecystectomy setup

-

Key “emergency items” for hemorrhage, retained sponge, power failure

-

Surgeon-specific reminders (tower height, implant sets, special instruments)

-

Crisis role reminders for scout nurses (e.g., airway emergency support flowchart)

This wouldn’t replace training or mentorship—but it would complement it, much like the QRH supplements the pilot’s training.

🧩 Final Thoughts

Learning in the operating room is layered. It happens through experience, observation, and repetition—but it’s also selective. Some things stick. Some don’t. And that’s normal.But what if we gave our brains the same scaffolding we give our pilots?

“In the operating room, just like in the cockpit, it’s not about memorizing everything—it’s about knowing what matters most, and what to do when everything goes wrong.”

I’m still learning. Still embedding. Still forgetting the occasional monitor and print settings. But I’ve come to respect that our memories are shaped not just by what we do, but by how we practice.

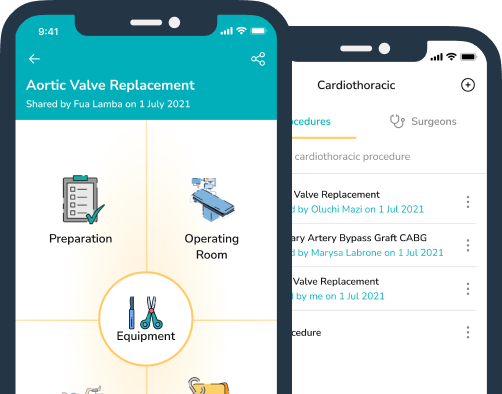

Platforms like ScrubUp help support surgical teams by providing accessible, step-by-step checklists and case preparation tools — enhancing safety, recall, and role clarity under pressure.

🛠️ We Need Systems That Support the Whole Surgical Team

In the operating room, we work in an environment surrounded by cutting-edge technology—robotic arms, real-time imaging, automated charting systems—all designed to support the surgeon, the anesthetist, and ultimately, the patient. But where are the systems that support us—the operating room nurses, surgical technologists, scrub scouts, and circulators? We absorb knowledge on the go. We adjust to new teams daily. We troubleshoot unfamiliar equipment mid-case. We remember thousands of details—until one slips through under pressure.