Instrument nurses anticipate, troubleshoot, and act quickly under the direction of the surgeon and surgical team. This readiness is not spontaneous—it’s practised, structured, and supported by systems that make efficiency possible.

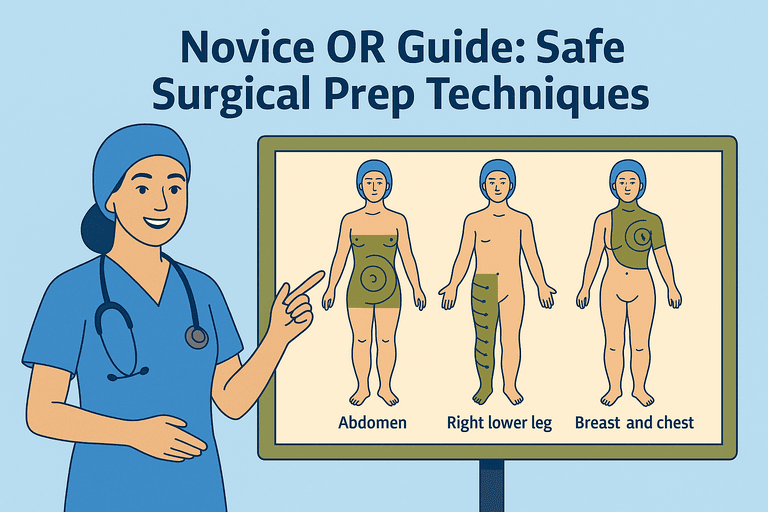

Which is why it’s essential that supplies are restocked, accessible, and organised in a way that supports those using them. When instruments and equipment are easy to locate, workflows become smoother, communication clearer, and patient care safer.

Healthcare facilities are unique. Multiple surgeries often take place at the same time, across different specialties and with varying surgeon preferences. Balancing and anticipating the requirements of each case can be challenging. The ability to maintain surgical flow depends on robust systems that support real-time visibility of supplies, streamline communication, and ensure that all teams can access what they need—when they need it.

In critical moments, seconds matter. Organisation, preparation, and anticipation aren’t just about tidiness—they’re about saving time, reducing stress, and optimising outcomes.

The best teams don’t just react; they prepare.

Evidence Supporting Organised Workflows in the OR

🧩 Human Factors & Cognitive Load

Operating rooms are complex, high-stakes environments where even small inefficiencies increase cognitive load and the likelihood of error. Research in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (2018) found that structured equipment layouts improve situational awareness and reduce team stress, particularly during intraoperative crises.

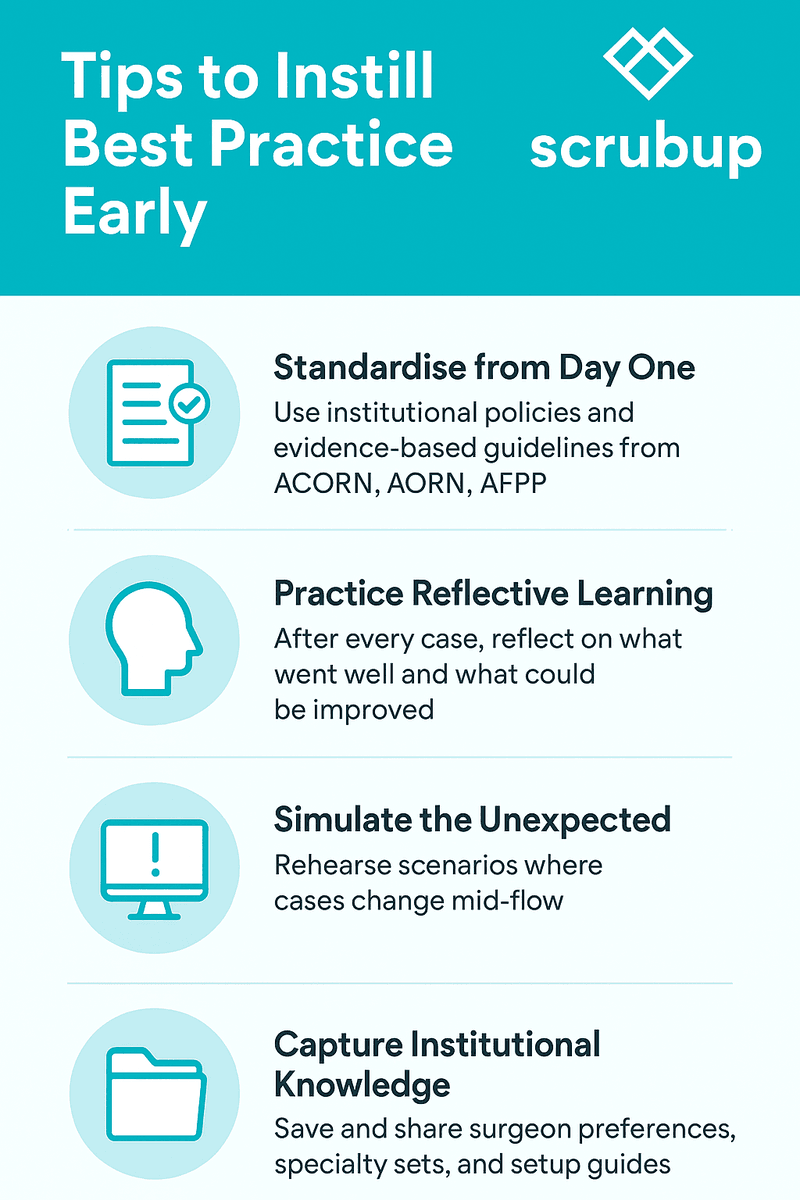

🏥 ACORN, AORN, EORNA, AfPP & ORNAC Standards

Global perioperative standards—including those from ACORN, AORN, EORNA, AfPP, and ORNAC—all recognise that organised, accessible, and standardised supplies underpin surgical safety and efficiency.

These organisations advocate for environmental readiness, equipment control, and preparation practices that enable clinicians to respond effectively when events change rapidly.

-

AORN Guidelines for Perioperative Practice (2024) highlight the impact of organised sterile fields on reducing inefficiency and risk.

-

ACORN Standards for Perioperative Nursing (2023) emphasise stock control, setup, and environmental preparation as foundational to safe surgical care.

-

EORNA Best Practice for Perioperative Care (2023) promotes safety through standardised processes and structured preparation.

-

AfPP Standards and Recommendations for Safe Perioperative Practice (2022) outline best practice in equipment accountability and intraoperative safety.

-

ORNAC Standards, Guidelines and Position Statements (2021) provide comprehensive frameworks for perioperative readiness across Canadian healthcare settings.

⏱ Efficiency and Patient Safety

Studies indicate that missing or misplaced instruments can delay procedures by 10–20 minutes per case (BMJ Quality & Safety, 2019), compounding anaesthesia time and risk exposure. Efficient organisation reduces these delays and enhances both safety and morale.

🧭 Crisis Resource Management (CRM)

Borrowed from aviation, CRM focuses on anticipation, communication, and structured preparation. Maintaining a “ready environment” mirrors a pilot’s pre-flight checklist: ensuring all essential items are accessible before takeoff—or incision.

Conclusion

Efficiently stocked and accessible supplies don’t just support the team—they protect the patient.

Organisation in the operating room isn’t housekeeping—it’s clinical readiness, situational awareness, and patient safety in action.

In a busy theatre environment, where multiple procedures occur simultaneously, robust systems that streamline stock management, standardisation, and communication are key to keeping teams safe, focused, and efficient.

Short Reference List

-

AfPP Standards and Recommendations for Safe Perioperative Practice (2022)

-

Journal of the American College of Surgeons (2018) – Human Factors in Surgical Performance

-

BMJ Quality & Safety (2019) – Impact of Missing Equipment on Surgical Efficiency