⭐ A Personal Note on Perioperative Practice

Every day in the operating room, perioperative professionals carry an extraordinary level of awareness and responsibility. Our roles — whether as nurses, surgeons, anaesthesiologists, surgical technologists, ODP’s or surgical assistants — require us to think about far more than the technical steps of a procedure.

We are constantly managing:

-

the safety and comfort of our patient

-

the surgeon’s needs and the flow of the operation

-

sterility, equipment, instrumentation, and positioning

-

oxygen levels, fire risks, energy devices, and electrosurgical safety

-

implants, allergies, comorbidities, medications, and documentation

-

communication across multiple teams

-

and the unexpected events that can arise at any moment

This level of complexity is part of what makes perioperative practice so unique — and so demanding. Electrosurgical and airway safety are only one piece of our daily responsibilities, yet they require constant vigilance and teamwork. A single decision, moment of inattention, or missed communication can have serious implications for patient safety.

What keeps patients safe is not any one person, guideline, or device.

It is the collective, coordinated awareness of every member of the surgical team.

This blog reflects the real clinical reality we face every day:

that perioperative care is a blend of technical skill, professional judgement, continuous learning, and shared responsibility. These high levels of awareness are the quiet work we do every single day to protect our patients — often without them ever knowing.

Electrosurgery is an essential tool in modern surgery, enabling effective cutting, coagulation, and hemostasis. But despite its benefits, electrosurgery carries real risks — including patient burns, fire hazards in oxygen-rich environments, alternate-site current injuries, and complications involving metal implants and external monitoring devices such as CGM sensors.

Improving safety requires situational awareness, strong communication, proper equipment use, and ongoing education. This blog highlights key risks, best practices, international standards, and emerging considerations for perioperative teams.

🔎 Understanding the Risks of Electrosurgical Burns

Electrosurgery-related burns arise from:

-

Poor grounding pad adhesion

-

Incorrect pad placement over hair, scars, or bony prominences

-

Insulation failure of laparoscopic instruments

-

Capacitive or direct coupling

-

Alternate current pathways involving metal implants such as hip or knee replacements, plates, and screws

These injuries can be deep, severe, and require further surgery — nearly all preventable.

Fire Risk in Oxygen-Enriched Settings

During head, neck, and airway procedures — especially under sedation — oxygen accumulates under drapes. In combination with electrocautery, this forms the fire triangle:

Ignition (ESU) + Oxygen + Fuel (drapes, alcohol prep)

Consequences may include facial burns, airway injury, and equipment damage.

🔒 Oxygen & Airway Safety (AST & ASA Best Practice)

Safe electrosurgery near the airway is a team responsibility shared by surgeons, anaesthesiologists, nurses, and surgical technologists. Both the Association of Surgical Technologists (AST) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) provide clear guidance to reduce surgical fire risk in oxygen-enriched environments.

AST Key Recommendations

-

Keep oxygen concentration below 30% whenever possible.

-

If higher oxygen is required, avoid open delivery systems and consider ETT or LMA.

-

Stop or reduce supplemental oxygen or nitrous oxide for at least one minute before activating electrosurgery, battery-powered cautery, or lasers during head, neck, and upper-chest procedures.

ASA Practice Advisory

-

Surgeons must alert anesthesia before activating any ignition source.

-

Anesthesia must alert surgeons if oxygen concentration is elevated or if an oxygen-enriched atmosphere is present.

-

Reduce oxygen to the lowest level that maintains safe saturation whenever clinically feasible.

Why this matters

These recommendations help all perioperative professionals minimise ignition risk, coordinate timing, and maintain safe oxygen practices when using electrosurgery near the airway.

Metal Implants & External Metal Devices

Perioperative teams must confirm the presence and location of:

-

Joint replacements

-

Orthopaedic plates, screws, rods

-

Cardiac/neurostimulators

-

Metal-backed electrodes

-

Diabetic glucose-monitoring systems with metal components

These items may unintentionally divert electrical current and cause burns.

⭐ Global Consensus

Every major organisation agrees:

Electrosurgery safety is a non-negotiable core competency for all perioperative practitioners — nurses, surgical technologists, and assistants.

This includes:

-

ESU physics

-

Pad placement

-

REM monitoring

-

Implant/CGM identification

-

Fire prevention

-

Airway safety

-

Insulation failure recognition

-

Oxygen management

-

Documentation and communication

What the data actually shows (2020–2025)

There is no single global registry that counts “all ESU burns” per year, so we have to pull from several reliable signals: medico-legal claims, sentinel event reports, and national safety alerts. All of them agree on one thing: burns and fires from electrosurgery are real, ongoing, and under-reported.

United Kingdom (NHS Resolution – diathermy burns)

NHS Resolution FOI data for England & Wales show clinical negligence claims where diathermy burns were the primary cause:

-

2018/19 – 40 claims

-

2019/20 – 26 claims

-

2020/21 – 22 claims

-

2021/22 – 17 claims

-

2022/23 – 23 claims

- 2023/24 – 21 claims

So from 2020/21 to 2023/24, there were around 20–25 closed claims per year specifically for diathermy burns in England and Wales alone. These are only cases serious enough to progress to a claim, so they almost certainly underestimate the true number of burns.

United States (energy-device injuries & surgical fires)

For the US, data sources point to both burn injuries and surgical fires where ESUs are the main ignition source:

-

A MAUDE database analysis of surgical energy-based device injuries (1994–2013) found 3,553 injuries and 178 deaths; thermal burns were 63% of injuries (~2,353 cases), and dispersive-electrode burns were a major mechanism. PubMed+1

-

This is older but still the key reference used in guidelines; there’s no newer 2020–2025 MAUDE summary yet.

-

-

A national review of surgical fires in the US from 2000–2020 identified 565 surgical fire events causing harm over 20 years (median 25 per year); in 82% of these, an electrosurgical device was the ignition source. ScienceDirect

-

A 2024 continuing-education article summarising Joint Commission data reports that from 1 Jan 2018 to 29 March 2023, 85 sentinel events related to fires or burns during surgery or procedures were reported, and notes that around 70% of surgical fires are caused by electrosurgical devices based on ECRI data. ast.org+2pedsurgeryupdate.com+2

Again, these are only the tip of the iceberg (fires and serious burns that get reported centrally), not every minor or moderate ESU burn is reported.

Australia (NSW & Victoria – incidents and sentinel events)

Australia doesn’t publish a national annual count of ESU/diathermy burns, but safety alerts and sentinel-event frameworks show clear concern:

-

NSW Health Safety Notice SN 013/23 reports a laparoscopic case where degraded insulation on a diathermy electrode caused a bowel burn requiring further surgery. NSW Health

-

The updated Safety Notice SN 020/25 notes that 10 additional incidents involving insulated laparoscopic instruments were reported across NSW since the original notice, prompting a strengthened response. NSW Health

-

Safer Care Victoria’s 2024 Sentinel Event Guide explicitly lists “in theatre diathermy accident or burn or where there is an explosion or fire” as a reportable sentinel event – meaning even a single case is treated as very serious. Better Safer Care

So, while we don’t have a neat “X per year” number for Australia, we do have clear evidence of ongoing patient harm, enough to drive repeat safety notices and inclusion as a sentinel event.

📌 IMPORTANT: Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) in Surgery

With increasing community use, many patients arrive for surgery wearing CGM sensors, such as:

-

FreeStyle Libre

-

Dexcom

-

Medtronic Guardian

These devices contain metallic components, which can behave like unintended electrodes during monopolar electrosurgery, posing burn and interference risks.

⚠️ Device Interaction & Burn Risk

-

Manufacturers instruct removal before diathermy.

-

Research demonstrates increased tissue heating around metal implants/sensors with monopolar ESU.

-

Case reviews recommend positioning CGM away from the diathermy arc and considering alternative devices.

-

Mechanism mirrors documented ECG-electrode burns.

🧑⚕️ Perioperative Recommendations

-

Ask all diabetic patients about CGM use.

-

Document location and remove before ESU use.

-

If not removable:

-

Keep the device outside the current pathway

-

Place dispersive pad to route current away

-

Prefer bipolar or ultrasonic devices

-

Include in the surgical time-out:

“Is the patient wearing a CGM or metal glucose sensor?”

📝 CGM Safety Action Plan for Surgery

1. Inform the Healthcare Team. Patients must tell their surgeon, anaesthetist, and perioperative nurse if they wear a CGM device.

2. Remove the Device Before Surgery. Stop the current sensor session and remove all wearable components before entering the OR.

3. Monitor Glucose with Fingerstick While Removed. Use a standard glucose meter for monitoring and treatment decisions while CGM is off.

4. Replace the Sensor After Surgery. Apply a new CGM sensor after the procedure and confirm accuracy using a fingerstick glucose test.

5. Follow Manufacturer Guidance. Refer to official Dexcom, FreeStyle Libre, or Medtronic instructions for removal and replacement.

🧑⚕️ Best Practice Principles for Safe Electrosurgery

1. Pre-operative Screening & Communication

- Identify metal implants, CGM sensors, and piercings.

- Communicate clearly during team briefings.

2. Correct Grounding Pad (Dispersive Electrode) Placement

- Apply to clean, dry, hair-free skin

- Choose large muscular areas

- Avoid scars, prostheses, bony areas

- Recheck after repositioning

- Document placement

3. Return Electrode Monitoring (REM): Audible Alarms Matter

- REM provides an audible tone confirming contact.

- Loss of contact triggers a loud alarm and cuts monopolar output.

- ESUs may be placed out of view — making audible cues essential.

- Audible alarm can be turned up or down, volume button is usually situated at the back of the ESU.

4. Safe Use Near the Airway

- Minimise open oxygen

- Use lowest flow possible

- Allow oxygen to disperse before activation

- Apply suction under drapes

- Keep sterile water ready

5. Choosing the Safest Energy Modality

- Prefer bipolar

- Use advanced bipolar or ultrasonic devices when implants/CGM present

- Avoid monopolar cautery near oxygen-rich environments

6. Education, Competency & Culture

Structured, ongoing training reduces preventable harm from burns and fires.

All perioperative staff, connecting ESU leads should be aware of Patient Safety and ESU protocols.

🌍 International Standards & Best Practices for Electrosurgery Safety

Safe ESU use is considered a mandatory competency worldwide. Major perioperative organisations outline strict expectations for education and practice.

AORN — USA

AORN’s Guideline for Safe Use of Energy-Generating Devices requires:

- Mandatory ESU/energy-device education

- Competency verification

- Fire-prevention protocols

- Standardised ESU setup and REM response

- Annual competency review

ACORN — Australia

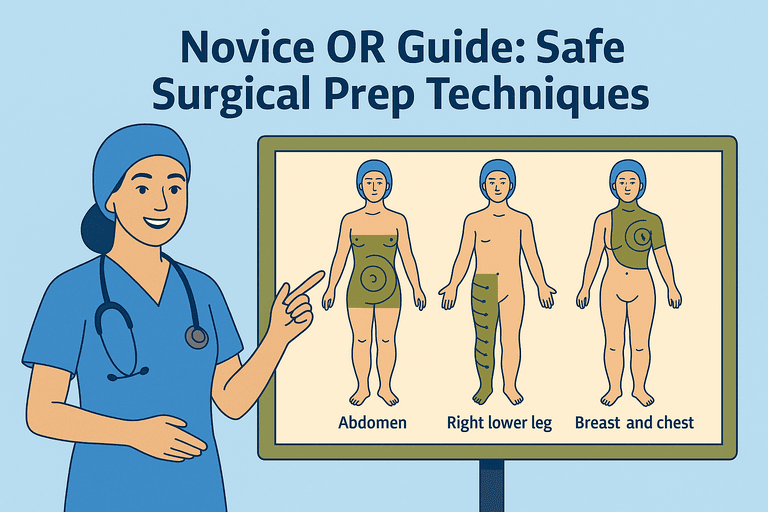

ACORN’s Standards for Perioperative Nursing include Electrosurgical Safety as a core clinical standard:

- Monopolar/bipolar principles

- Safe pad placement

- Preventing alternate-site burns

- Airway & oxygen management

- Novice nurse education through Fundamentals of Intraoperative Nursing

AfPP — United Kingdom

AfPP’s standards emphasise:

- Training & competency assessment

- Equipment checks and risk management

- ESU safety as part of routine clinical audits

ORNAC — Canada

ORNAC’s guidelines identify ESU safety as:

- A foundational competency for perioperative RNs

- A required component of approved perioperative education programs

- A standard requiring annual review and validation

EORNA — Europe

EORNA’s Best Practice for Perioperative Care includes a full electrosurgery section covering:

- Generator checks

- REM

- Burns from implants, piercings

- Fire and oxygen risk

- Safe handling of energy devices

AST / NBSTSA — Surgical Technologists (USA)

Surgical technology bodies require competency in:

- ESU setup

- Pad placement

- Cautery-pencil safety

- Insulation-failure identification

- Fire prevention

- Alternate current pathway risks

References

- AORN. Guideline for Safe Use of Energy-Generating Devices. In: Guidelines for Perioperative Practice. Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, USA.

- ACORN. Standards for Perioperative Nursing in Australia – Electrosurgical Safety Standard; Fundamentals of Intraoperative Nursing education resources. Australian College of Perioperative Nurses, Australia.

- AfPP. Standards and Recommendations for Safe Perioperative Practice. Association for Perioperative Practice, United Kingdom.

- ORNAC. Guidelines for Perioperative Nursing Practice in Canada. Operating Room Nurses Association of Canada.

- EORNA. Best Practice for Perioperative Care – Electrosurgical Safety section. European Operating Room Nurses Association.

- AST / NBSTSA. Core Curriculum for Surgical Technology and NBSTSA Certification Examination Content Outline – Surgical Energy and Electrosurgical Unit (ESU) Safety. Association of Surgical Technologists / National Board of Surgical Technology and Surgical Assisting.

- NHS Resolution (UK). FOI 6813 – Diathermy burns / reaction to prep – hospital-acquired infection claims data (2018/19–2023/24).

- NHS Resolution (UK). FOI 6278 – Diathermy burns – clinical negligence claims/incidents (2017/18–2022/23).

- NSW Health. Safety Notice SN 013/23 – Risk of burn injury from degraded insulated laparoscopic instruments. New South Wales Health, Australia.

- NSW Health. Safety Notice SN 020/25 – Further incidents involving insulated laparoscopic instruments. New South Wales Health, Australia.

- Safer Care Victoria. Victorian Sentinel Event Guide 2024 – In-theatre diathermy accident or burn, explosion or fire as a reportable sentinel event. Safer Care Victoria, Australia.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). MAUDE database analysis of energy-based surgical devices – injuries, deaths and proportion of thermal burns.

- ECRI Institute. Surgical Fires in the Operating Room – root causes and contribution of electrosurgical devices as ignition sources.

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Data Summary (2018–2023) – Fires and burns during surgery and procedures.

- Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA). Intraoperative burns: learning from medico-legal cases – analysis of 53 intraoperative burn cases (2012–2016).

- CMPA. Surgical fires: managing the risks – summary of 54 medico-legal cases related to surgical fires in Canada.

- Health Canada. Medical Device Recall Notices – Patient return electrode pads used with electrosurgical units (2023–2024).

- Ontario Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development. Alert: Preventing Surgical Fires in Hospital Operating Rooms (updated 2025).

- Abbott Diabetes Care. FreeStyle Libre Sensor – Important Safety Information (diathermy and high-frequency electrical treatment warnings).

- Dexcom. Dexcom Continuous Glucose Monitoring System – Safety Information (guidance regarding electrosurgery and imaging).

- Medtronic. Guardian / Medtronic CGM Systems – MRI and diathermy safety guidance.

- Studies examining tissue heating around metallic implants and glucose sensors during monopolar electrosurgery, demonstrating increased local temperature near metal.

- Electrosurgical safety literature describing ECG-electrode and external-electrode burn mechanisms caused by high current density and unintended alternate pathways.

- Case reports and reviews of electrosurgical pad burns, insulation failures, alternate-site burns and oxygen-related fires in head and neck / airway surgery.

- SAGES. Fundamentals of the Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE) – educational program highlighting common knowledge gaps in surgical energy safety among surgeons and perioperative clinicians.

- Association of Surgical Technologists (AST). Guidelines for Best Practices: Safe Use of Energy Devices. AST Standards of Practice for Surgical Technology and Surgical Assisting. (Includes recommendations for oxygen management, reducing oxidizer concentration, and pausing oxygen flow ≥1 minute before using electrosurgery or lasers during head, neck, and upper-chest procedures.)

- American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). Practice Advisory for the Prevention and Management of Operating Room Fires. ASA Task Force on Operating Room Fires. (Provides guidance for ignition-source control, team communication, and safe oxygen practices during electrosurgery and airway procedures.)